CHAPTER 1: THE EARLY YEARS

Formalized changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure with regards to eDiscovery were made in December of 2006 as the culmination of a period of debate and review that started in March 2000. Prior to those codified changes, there were several landmarks in the development of the eDiscovery space.

The first was a series of discovery decisions in a lawsuit which became popularly known as the Zubulake case. (Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, 220 F.R.D. 212 (S.D.N.Y. 2003). Throughout the life of that case, the plaintiff claimed that the evidence needed to prove the assertions in her complaint existed in emails stored on the computer systems of the defendant. She had copies in her possession of some of those messages and when the defendants were not able to produce the originals the court found that it was more likely than not that they existed. Further, since the defendants corporate counsel had directed that all potential discovery evidence, including emails, be preserved, the court held that the employees who received that directive were negligent in fulfilling their duty of preservation and levied significant sanctions against UBS.

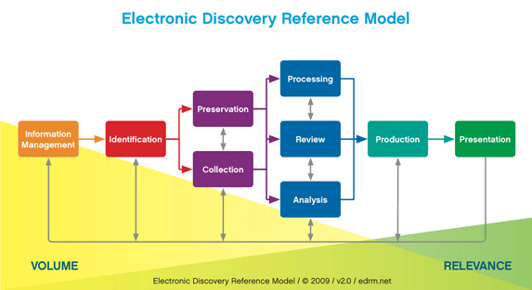

Shortly thereafter, in 2005, the EDRM (Electronic Discovery Reference Model) was formed by Atty. George Socha and his partner Tom Gelbmann as an open-source standard with the goal of facilitating leadership, standards, best practices, tools, guides, and test data sets to improve electronic discovery workflow processes.[1] George and Tom devised the following chart to show a general workflow for eDiscovery projects.

The problems pushing these changes forward were the increasing volume and multiplicity of data in electronic formats. Examples of the types of data included in eDiscovery are not just standard business documents such as letters, agreements, memos and even spreadsheets but also e-mail, databases, web sites, instant messaging and any other electronically information stored in the ordinary course of business that could be relevant evidence in litigation.

The increase in digital activity has become even more pronounced in recent years with more people using digital information in all areas of their lives and the increased number of people working from home, especially during the COVID pandemic.

According to a report from the Georgetown University Law School, 88% of the US population uses the Internet every day and 91% of the adults use social media regularly.[2]

Additionally, "raw data", such as deleted files or file fragments left in unused space on a computer which could be retrieved by forensic investigators is potentially relevant as may be the myriad of data backup types ranging from tape systems to hard drive archives.

According to the Smithsonian Institution Archives, most documents created today are generated in electronic format, we have seen an enormous rise in ESI in all case types. Litigators may review material from e-discovery in one of several formats: paper printed from images, PDF images (with or without searchable text)single- or multi-page TIFF images or the original format in which the documents was created and stored, the last type being commonly referred to as "native files".

That variety of file types and formats led to countless discovery disputes between the parties. Defense firms commonly objected to the perceived, or at least argued, shortcomings of native files. They preferred to use static images such as TIFF files, most often because they had invested in litigation support software systems that utilized that format. Plaintiffs preferred native files because they were most often a file type such as Word or a common email format that they already possessed and knew how to use.

These changes and the resultant tensions effectively forced civil litigants into a compliance mode with respect to their proper retention and management of electronically stored information (ESI). The risks that litigants then began to face because of improper management of ESI include spoliation of evidence, adverse inference rulings, summary judgment motions and sanctions, both monetary and procedural. In some cases, attorneys were even brought before their state bar association to answer to charges of misconduct., as was the case in the much discussed matter of Qualcomm Inc., v. Broadcom Corp., 548 F.3d 1004 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

This atmosphere and those type of disputes became part of the reason that the court rules were changed. The Rules Committee of the Federal court system felt it necessary to implement changes which would reduce time consuming arguments over file formats that were leading to delays in the handling of litigation matters. We will discuss those rule changes in the next section.

[1] In 2016, Duke Law School acquired the EDRM in order to expand the involvement of Duke Law’s Center for Judicial Studies as part of its mission to generate ways to improve the administration of justice. In 2019, Mary Mack and Kaylee Walstad, the former executive director and former vice president of client engagement, respectively, of The Association of Certified E-Discovery Specialists (ACEDS) acquired the EDRM from the Bolch Judicial Institute at Duke Law School.

[2] See Social Media Evidence in Criminal Proceedings: An Uncertain Frontier from Georgetown Law at https://www.crowell.com/files/Social-Media-Evidence-inCriminal-Proceedings-An-Uncertain-Frontier.pdf

g post content here…

-1.png?width=400&height=164&name=DWRLogoClassic%20-%20Copy%20(2)-1.png)

Comment On This Article